And the golden bees were making white combs, and sweet honey, from my old failures.

—Antonio Machado, translation by Robert Bly

Photo Credit: Andrew Dawes

Aspen Karen Fisher and I met in Ireland as members of a small tour studying ancient and current Irish shamanic practices. Shamanic practices are about transformation, often supportive of natural life passages, and usually fostered within community. We visited places of historic interest, and worked with people transforming old practices into new ones. This was a first tour for our two leaders, and when things did not go perfectly they thought they’d failed us. But we all were gathering pollen, and much honey was made from that falsely perceived failure.

For examplthingid’s eternal flame burned at Cill Dara (Kildare) before and after Christianity came. The goddess transformed into a Bishop, and the fire temple area became a monastery. Ten or so centuries later Henry VIII’s campaign against Roman Catholicism closed many religious houses and Henry confiscated their funds. People died. In Bridgid’s holy home the soldiers extinguished the eternal flame. In 1993 it was relighted in the Market Square in Kildare by Sr. Mary Theresa Cullen of the Brigidine Sisters. It is tended by the sisters today. They also foster Flamekeeping communities around the world.

Being a Flamekeeper is an Incarnated Practice

When we returned from Ireland Aspen, who was sponsoring a Bridgid’s Flamekeeping group, invited many of those on the tour to be part of that calendar. A Flamekeeper calendar group needs 19 people to respond. Each day of 19 a Flamekeeper lights a candle the evening before which burns through the night and the next day, and then is “blown forward” to the next Flamekeeper. Bridgid herself traditionally keeps the flame the 20th day. My husband and I took Days Eight and Nine.

Aspen keeps the calendar organized. Before Covid and Zoomland the calendar group met in person once a year on Imbolc (Feb 1-2), and Aspen would prepare a ritual followed by a potluck meal. Some years the calendar is more than 19 with two or three people for some days; some years some shifts are empty. We could frame the years with a lack of volunteers as a failure; instead, we assume Bridgid steps up. We could see missing our assigned days as a failure; instead we see an opportunity to discover why we forgot this part of our spiritual practice. The reason is often “too busy,” and we slow down.

Photo Credit: Cristina Marin

Bridgid and the Bees

One Imbolc ceremony several years ago was extremely important for me. The theme was Bridgid and the Bees. Bees might be a totem being for Aspen; she collects representations of bees in jewelry, ceramics, wood, weaving, paintings and pictures which reside on an altar in her home. Some of these items came to the Imbolc gathering to grace the center table, along with many beeswax candles. The ceremony included Aspen’s fascinating bee research, and powerful images in her narration and poetry. She touched on some of these themes, and I’ve since added others.

Beekeeping

Probably the first human collectors of honey followed the bear as a role model. Currently the first evidence of hives as we think of them appears in Egypt 5,000+ years ago.

Bees are in Trouble

There are at least 20,000 named bee species throughout the world. Some are tiny (2mm – Perdita minima) to ones as big as plums (carpenter bees). According to the Center for Biological Diversity the estimate is that one in six bee species are extinct regionally, and more than 40% are vulnerable to extinction. Around the world lots of people are working on this problem.

Nectar and Pollen

Bees seek and use both pollen and nectar. Nectar is made by plants (not all plants) to attract bees (and other insects). It provides energy for the bees. Pollen is powdery grains collected by the bee from bags on the filament on the anther on the stamen. While flying about they pollinate other blossoms.

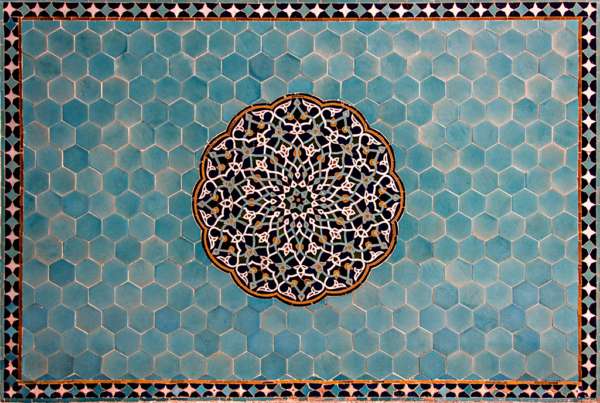

Honeycomb and Beeswax

I have tasted honey from a wax comb from inside a hive. The bees make it from oxygen, carbon, and hydrogen. The hexagonal structure and its sweetened strength are part of our literature (think Winnie the Pooh). Most of us have some bear and bee stories. The geometric perfection inspires, and appears in many artists work.

Photo Credit: Hamed Najafi

Buzz and Hum

We also make these sounds, even as babies we buzz, and we hum when we are happy. I was lucky to be in London’s Kew Gardens when I could go inside a 17 meter high HIVE installation. Standing inside it, I heard the sound from inside a hive. When I was inside the round tower (and other round towers since) I sounded a note, interested in what might happen. The round tower in Kildare is thought to be a bell tower, a place for religious worship, and obviously for defense (pull up the steps and shut the door). There’s a good blog with great pictures about the Kildare round tower. When I hummed inside the tower it reverberated beautifully. I am using this experience (expanded) in my fantasy trilogy based on the Goose Girl story. Other Images begun with Aspen’s Flamekeeper service have grown into a major storyline in the books.

Transformation to Honey

Pollen is not used to make honey. Here are four steps:

- Finding where the flowers with nectar are in the wide world

- House bees take the nectar inside the colony and pack it away in hexagon-shaped beeswax honey cells.

- The nectar becomes honey by creating air movement with their wings, which dries the nectar into honey.

- Once the honey has dried out, they put a lid over the honey cell using fresh beeswax – kind of like a little honey jar.

Photo Credit: Mika Baumeister

Making Honey from My Old Failures

Last night, as I was sleeping,

I dreamt — marvelous error!—

that I had a beehive

here inside my heart.

And the golden bees

were making white combs

and sweet honey

from my old failures.

This is the full stanza from the poem Last Night as I Was Sleeping by Anthony Machado, translated by Robert Bly. The poem holds three images of transformers: water, bees, and the sun. I think of the bees leaving their hive, going about their individual work, communicating as they need to, pollinating randomly as a gift to the plants, returning with the nectar to the hive. Maybe they experiment with different flowers, maybe they find some full of nectar and others empty. These are not failures, they are explorations. Next the hive (house) bees do their work, transforming nectar into honey, packing honey into the honeycomb. Do they “see” the honeycomb? Do we “see” our cells of work connected to others, all of us doing our best with what we have and are? Do we take our “failures” and transform them (and ourselves) into what’s needed now, for ourselves and the hive?

Make this leap—maybe we do this work on Day 8 and 9, and are unaware of the other 17 Flamekeepers tending the eternal flame. What if our work, both of our hands and our hearts, functions like cells in a honeycomb? Let’s trust that the other bees are doing their work. What if we trusted that the Creator tends the flame of life on the days we miss the mark?

And the last image of Antonio Machado’s poem is

Last night, as I slept,

I dreamt — marvelous error!—

that it was God I had

here inside my heart.

If we think of our failures as fuel for transformation, then failure points to learning, and learning to transformation. Transformation builds resilience. Resilience allows us to risk and fail, knowing we’ll keep learning and changing, that the Creator calls us to make the necessary honey in our heart.

Bridgid’s Blessing at Imbolc

Bridgid passes by bringing a blessing on Imbolc. You might write what you perceive as your failure on a piece of narrow cloth, put it outside for the blessing, and in the morning hang it on a branch of a tree or bush. Let the elements transform it, turn it into honey for your soul.

Here’s a prayer …

Let what I see as a failure yet be useful in the cycle of days.

Let what I did in haste or harm be blessed; let its healing heal all.

Let my forgetfulness and inattention turn into honey for my soul.

Let me Bee the transformer bringing the changes needed in my life and the world.

Photo Credit: Shelby Cohron

It’s Imbolc in the Northern Hemisphere, the Cross-Quarter direction between Winter Solstice and Spring Equinox. The four Cross-Quarter days are transformers, marking the time half way between the last Solstice and the next Equinox, or the last Equinox and the next Solstice. One season being left behind, one season coming in. We leave behind the 80 high holy days from Advent to Candlemas. We go now towards Equinox, Passover, Lent/Eastertide.