By Lola L. Wilcox and Helen Choi Fong

The word decision comes from Latin words meaning “to cut away”. Using the same root, the word “incision” means to “cut in”. To decide is to choose one alternative, with all others being “cut away”.

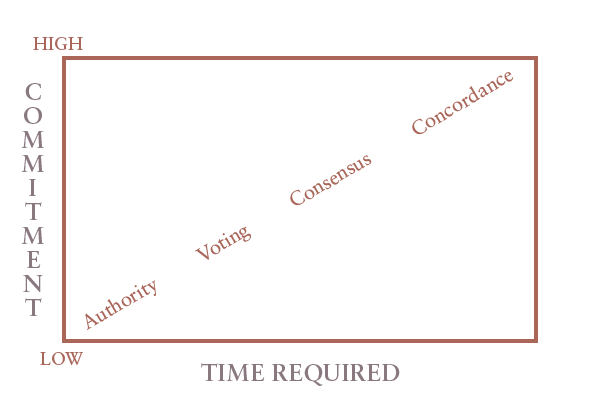

People often remark that they would prefer a commitment building decision method, such as consensus, but it “takes too long”. On the other hand, authoritative decision makers can lack critical information and alternative points of view, and poor decisions result. Four methods for decision-making are presented here with considerations and optimizing methods for success at “cutting away”. Methods for increasing the effectiveness of inclusive decision making methods receive special focus.

Critical First Questions

- Who has the authority to make the final decision?

- How quickly must this decision be made?

- What is the degree of commitment needed for implementation?

Any decision maker (individual or group) must determine up front the amount of authority allocated to make the decision. Determine who has the authority to make the final decision:

– the leader exclusively

– leader using a subgroup’s recommendations

– a subgroup

– the entire group?

Two criteria useful for selecting the most appropriate point to place the decision-making authority are the time available, and the degree of commitment needed. For any given situation, ask:

- How quickly must this decision be made?

- What is the degree of commitment needed for implementation?

Some managers believe all decisions should be made quickly. Others understand that building consensus first makes implementation a turn-key. A third variable is the decision-maker’s style preference; hopefully the leader is able to set personal preference aside and use the most effective method for the decision – the moment when all other options are cut away.

AUTHORITY DECIDES:

The person in authority makes the decision, and announces that decision to the group.

Considerations:

- When the matter being decided is obvious, the group generally responds with relief that the decision has been made and moves to implement it.

- When the decision is not obvious and opinions differ, but the matter is of little importance, the decision may be met with some grumbling but no real resistance.

- If the matter is of major importance, and people disagree with the decision, they will generally obey the decision, as any other course is costly to them personally. In that case, personal commitment is to survival, not to the decision.

- Some decisions are implemented that many knew would fail, but their knowledge was not included in the decision. Too many decisions like this encourage employee cynicism. Also, in practice, a decision may be met with resistance, and many months are spent in uphill selling of the decision.

In theory an authoritarian decision is made quickly. In practice, many months often go by while the “authority” sits on the decision; generally this waiting is because the “authority” knows there will be opposition, or the matter is not clear. The “authority” could have effectively used a commitment building process while waiting.

Optimizing the Authoritarian Method:

- Be sure critical information is included.

- Interview key people – this can be very quick, and save mistakes.

- Ask: what is the worst case that can happen and include a mitigation plan in the decision.

Announce the decision immediately to those effected:

- Let as many people know the decision at the same time as possible.

- Explain clearly the reasons behind the decision.

- Ask for questions and answer them honestly.

- Ask for emotional reactions: “How do you feel about this decision?” Listen and empathize with what people are feeling.

None of these actions require the decision maker to change the decision.

VOTING DECIDES:

Voting is a quick method of group decision making. The typical procedure is to have the majority, defined by greater than 50% of attendees (this % can vary, but never below 50%) determine the decision. Once every grade school child learned voting skills in Robert’s Rules of Order.

Considerations:

- Often two or more issues being voted on are not clearly stated and people discover afterwards they have misunderstood the fundamental issue.

- Voting from erroneous assumptions may diminish trust as people may feel tricked.

- Voting is a competitive process, forcing the group to compete internally.

- Voting encourages “either-or” thinking.

- Voting encourages argumentation rather than dialogue.

- Voting can split the group into “winners” and “losers”.

Optimizing the Method:

- Be sure that the issues being voted on are separated, and each is clear to all.

- Before the vote, surface underlying assumptions regarding the decision.

- Be aware that people who call for a vote believe their view can win now; those who resist a vote believe they will lose. Resist this impulse until the issue is defined and the options are clear.

- When the vote is over, encourage people to talk about how they feel. Respond with empathy.

- Request that people opposed to the vote move on and support the decision. Ask what they need to be able to do that.

Be aware that people who call for a vote believe their view can win now; those who resist a vote believe they will lose. Resist this impulse until the issue is defined and the options are clear.

Consensus and Concordance processes were once more clearly understood and skillfully practiced. They were used to help form the United States Constitution as many attendees were American Friends (Quakers) and highly skilled at these methods (Benjamin Franklin, for example). Native American tribes utilized many similar processes and their “constitutions” were studied as models.

Basic meeting skills are essential for these processes to succeed. Meetings can be third-party facilitated while people learn these skills.

Basic skills include:

- Listening, staying focused, encouraging all members to participate.

- Keeping the discussion on track; group members’ tasks include helping each other to stay focused.

- Limiting repetitive discussion by saying “That point has been discussed. Do you have anything new to add to it? If not, let’s move on.”

- Accepting a responsibility to never evade a critical issue (roll over).

- Presenting positions or discussion points lucidly, both with logical and emotional considerations, and as succinctly as possible.

- Paying attention to the reactions of the group, and using the reactions to clarify issues.

- Not “arguing”, pressing an opinion, raising the voice to dominate. This is not a competition.

CONSENSUS DECIDES:

The decision is reached when individuals are in fundamental if not complete agreement and will “support the decision.” A “decision” supporting an individual position isn’t the desired outcome: it is not a competition. The task is to determine what is right for the group or task, not for the person or individual view. Decision time is at a point where all the different views have been understood and responded to by the group, and the best course of action is apparent to most participants. American Friends call this moment of realization reaching “the sense of the meeting”. Any remaining opponents to the decision are asked respectfully “to stand aside” (see process below).

Considerations:

- Excellent process when there is no clear expert and different relevant information is held by different group members.

- Disagreements help promote better decisions; range and variety increases probability for more innovative decisions and strategies.

Optimizing the Method:

- Conduct the meeting with care, giving attention to the dignity of each person and point of view.

- Avoid interminable discussion and respect the need to reach a decision.

- The meeting is conducted with the same efficiency as one under Robert’s Rules of Order. Each member has three responsibilities: to express own convictions, to be open to different ideas, and to achieve the group’s goals.

- Get as much information as possible as quickly as possible.

- Be skeptical of early, quick, easy agreements and compromises.

- Yield only when convinced rationally and emotionally. People must not change positions just to avoid conflict or for the sake of harmony or personal promotion.

- Surface and discuss underlying positions and assumptions.

- Prevent techniques such as averaging or bargaining to reduce conflict.

- Use stalemates to push for new alternatives not yet considered.

- Late in the meeting dissenters must seriously consider whether to hold up consensus by continuing to persuade, or to stand aside.

Standing Aside: If all information has been presented and digested and recent discussion has not yielded new critical points previously neglected, a dissenting person should only hold up the group in an extreme case. If the sincere conviction of most of the group is clear, and it is not a life-or-death matter, the dissenter should “stand aside.” The facilitator or a member of the group may help by summarizing the process and outcomes so far. An example: “There seems to be for most people a decision for (name it), but this opposing opinion(s) is not resolved (name it or them). Would you who hold the opposing opinion be willing to stand aside so that agreement can be reached?” Minutes include the decision and a list of those who stood aside.

CONCORDANCE DECIDES:

Each individual must enthusiastically support the decision without reservation. The process can look exactly like Consensus but the entire group has reached agreement.

Differences of opinion are critical to the process and encouraged as helpful for clarification of issues and strategy building. The group is asked to consider every aspect of the discussion. At the beginning people will share what they know, including concerns and what they believe the decision should be. Once everything that each individual knows is shared, the right decision may be apparent to all, or it will be time for the conversation to explore blended or creative solutions.

“We just keep talking until there’s nothing left but the obvious truth.”

– Oren Lyons, Turtle Clan, Onondaga Iroquois

Considerations:

- Ensures greatest opportunity for dialogue and commitment.

- Entire group is committed to final decision.

- The group must trust that resistance brings clarity – group pressure on individuals or to conclude the process prematurely must be prevented.

- Individuals in the group must be able to stand alone if necessary to represent their concerns to the group

Optimizing the Method:

This specialized Concordance process may look like voting, but the goal of each polling round is to identify topics for further discussion.

- Facilitated process by a neutral party is essential.

- A short review of how concordance works is helpful.

- State the initial decision to be made, which has been clearly defined.

- Take a first round poll: yes or no or have questions/comments. The group is polled in every case individual by individual. The facilitator can use an aid such as Green/Yellow/Red cards (see appended technique). The group will be interested in the initial results.

- No judgment is made. If one person dissents, it is the group’s responsibility to understand this person’s reasoning or guidance. One point may be so imperative that, once it is understood, the entire group shifts position.

- The facilitator calls on the individuals in the smallest decision group first (Yes, No, or Questions/Comments). Each individual speaks and answers questions for as long as is needed to ensure understanding.

- The facilitator could chart: Issues, Questions, Data, Other Solutions. Charting is not encouraged, but the group may find it helpful.

- The facilitator may observe to the group that the decision as currently phrased is no longer valid, and ask for suggested new wording.

- After full discussion there is another polling. Again, each individual speaks and answers questions. The discussion centers on helping to dig out the issues and assumptions, and developing strategies that will minimize the issues’ impact.

- After full discussion there is a third polling, followed by discussion.

- If the discussion goes over three polls it is very useful to break, if possible overnight, before the fourth discussion and poll. This gives time for the discussion to settle down, issues to clarify, and offers a little time for individuals to make any emotional shift required.

Additional Techniques:

Tension is too high.

You have two options: increase it or break it. Increasing it means you apply pressure: “We only have ten more minutes to make this decision.” or “If we can’t decide this, we’re not going to meet our goal and get done today.” Breaking it includes anything from calling a ten minute break to asking for two minutes of silence. If you call for silence, enforce it. A variation is to have you talk them through the silence – have people close their eyes and relax, take some deep breaths, then come back to the issue at hand mentally. Ask “What is it that is critical here, what is it that can be given up?” You can also break people until later or the next meeting on a given issue: “We are not clear about this. We’ll put it aside until the next meeting.”

Blocking:

In concordance decision making a single individual or small group may not be able to shift. The facilitator might inquire if the person or group speaks on behalf of the best interest of the group, and not a personal value and belief. If the person speaks for the best interest of the group, have them express why and what decision they would like instead. Poll the group on that decision. If the dissenter’s decision is not supported, ask the person to withdraw opposition. If the person will not, ask the group if they wish to go to a consensus decision, and have the person(s) noted as “standing aside”.

Dr. Leroy Little Bear’s Dialogue Process

In this powerful concordance seeking model, a topic is proposed in advance for exploration, and people representing as many points of view on the topic as possible are invited. They are seated in a circle and some attention is paid to a diverse seating order. Dr. Little Bear begins facilitation by stating the topic clearly, and the “rules of engagement”:

- There is no ending time to the meeting. People come prepared to spend as long as needed (usually a long weekend).

- Each person may speak as long as is necessary

- No person, having spoken, may speak again (it is not a discussion)

The first person to Dr. Little Bear’s left begins, addressing the topic from that individual’s specific point of view. The person speaks for ten minutes or an hour… The next person includes or responds to the first person’s key points while speaking. The third person includes both previous speakers’ points while speaking. And so it goes for thirty or more people. Other people are sitting in an outside circle listening.

Breaks are taken for stretching, meals, and sleeping.

A concordance of understanding is built in the center of the circle; at times it feels like a living entity created by the power of listening and including the previous speakers points while having the time to make one’s own.

Imagine this conversation happening with a topic of the Future of Oil. Invitations would be to oil company presidents and board chairs, fracking opponents, international political strategists, earth scientists, chemists determining new uses for oil, perhaps children and animals or their representative. Each speaker incorporates the point of view of the people who previously spoke.

The idea of including a person who represents those who cannot speak for themselves but are affected by the decision is gaining ground. Who speaks for children? Species? Water? Earth? Space?

Large Group Decision Making Methods:

Information sharing and decision-making methods for large groups of people (50 to 1500) have been developed. A brief list of these methods is included so that possibility may be explored if appropriate.

- Future Search: Conferences have group decision making processes that are based in consensus and concordance techniques. (Weisbord, Janoff, Emery)

- Fishbowl: A sub-set of a large group sits in the middle with one chair open for any other person to join the fishbowl group for a short period to make a point. The people in the fishbowl represent the various viewpoints of the discussion. The decision is determined by either the fishbowl or the whole group, usually by consensus.

- Nominal Group Technique: A voting method where all group members’ input is valued through a series of tallies. Each member gives a point of view.

- Duplicates are combined. Then group members rank the solutions. This may go more than one round. There are many variations. (Delbecq, VandeVen, Vedros)

- Talking Stick: Native American based method of passing a stick or rock or the microphone from person to person until all are heard. Usually by the third or fourth round many people pass the stick to the next person. When the stick goes around with no one speaking, the decision is stated and agreement noted.

- Distributed: Decision making is distributed to the part of the hierarchy best suited to make the decision.

Conclusion:

Any leader or group can use Authority, Voting, Consensus or Concordance decision making methods efficiently. As the last two of these methods yield high commitment, it is to the benefit of all that each person becomes skilled in these methods.

Bibliography

– Consensus Building by Caroline Estes; a one page summary for Boulder Friends Meeting.

– Group Consensus: a one page list of methods from the Center for Creative Leadership.

– Human Synergistics International. Synergistic Decision Making; instruments like Desert Survival.

– Reflections on Friends’ Business Meetings. Jack Powelson, with contributions by Robin Powelson and Gilbert White.

– Seed Conference, Albuquerque

– Thomas Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument

– Teams: Eunice Lawrenz’ Beth Israel Redesign team. Public Service Company’s Organization Development team, Lawrence Livermore (CA).

Wikipedia